Inflation & RBI’s new monetary framework

LEKHA CHAKRABORTY, Professor, National Institute of Public Finance and Policy, New Delhi, India. email:lekha.chakraborty@nipfp.org.in

KUSHAGRA OM VARMA, Intern, National Institute of Public Finance and Policy, New Delhi, India.. email:kushagra.verma@nipfp.org.in

|

The Reserve Bank of India and the Central Government's signing an agreement in February 2015 to devise a ‘New Monetary Framework’ is potentially a radical transition in the operation of monetary policy in India.

The new framework deals with how monetary policy ought to be conducted in India and intends to give greater autonomy to the central bank to focus exclusively on price stability. Specifically, the new framework stipulates that the central bank should conduct inflation-targeting and that the tool to control inflation should be the ‘policy rate’ (popularly, the ‘repo rate’) that it directly sets through a monetary rule. This had been earlier recommended by the expert committee to “Revise and Strengthen the Monetary Policy Framework”, constituted by the RBI in 2013. The recent draft Indian Financial Code (IFC) further emphasised the need to adopt inflation targeting as the sole objective of monetary policy in India.

This is a significant transition in the conduct of monetary policy in India away from the erstwhile “multiple indicators approach” where the RBI had given equal importance to economic growth and inflation containment. The key question is -would RBI be able to control inflation through its new monetary policy rule?

Our Framework: Is inflation a monetary phenomenon in India?

Against the backdrop of the new monetary policy framework, we, in Chakraborty and Om Varma (2015), on which this One pager is based, analyse the determinants of inflation in the deregulated financial regime. While stylized facts attribute the rise in inflationary pressures to supply and demand factors, we noted that the lack of meaningful analytical frameworks thwarts the systematic empirical analysis of this aspect. The inflationary phenomenon in India is complex, and the analytical framework is bound to be “eclectic” in the sense that it cannot be determined within the neat monetarist or fiscalist model categories, as monsoon failures or global oil shocks can trigger inflation.

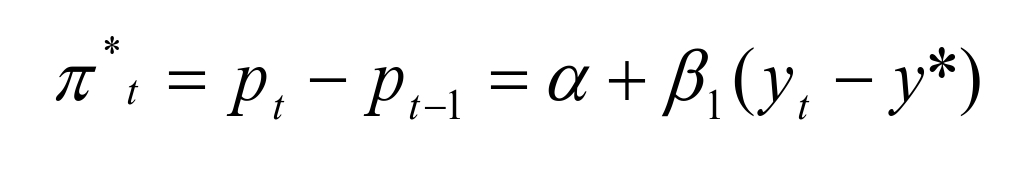

Having said that, we set our aggregate supply schedule, as explicated in equation (1), which depends on the output gap – the deviation of actual output (yt) from the potential output (y*)in the economy.

(1)

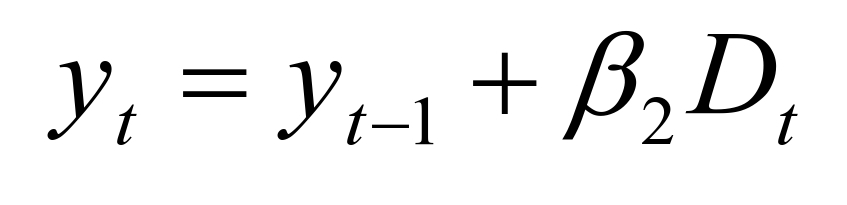

We specify the aggregate demand function as a set of demand-shift variables like monetary and fiscal policies and the variations in the external sector (equation 2), where Dt is inclusive of seigniorage (the change in reserve money to GDP), ex-ante real rate of interest, fiscal deficit and variations in capital flows.

Empirical studies suggest that “money” may play a partial but crucial role in determining the dynamics of price movements in India. Deducting y* from both sides of the equation (2) and applying it to equation (1), we get the analytical framework, where we incorporated rainfall in July to capture the supply-side effects (for details, see Chakraborty and Om Varma, 2015).

|

Our Results: Supply side factors significantly determine inflation

Using the ARDL methodology, the determinants of inflation based on Wholesale Price Index (WPI) and the Consumer Price Index (CPI) have been empirically tested for the financially deregulated period. The study finds that the supply-side variable - July rainfall (-1.21 percent) is relatively significant and has a considerable effect on CPI inflation, when compared to output gap (-0.09 per cent), fiscal deficit (0.68 percent) and real interest rates (-0.01 per cent). The “money” (seigniorage) was found insignificant in determining CPI inflation. The results hold the same for WPI inflation, with the exception that “money” was found relevant in WPI models, though relatively insignificant in their impact when compared to supply-side variables. The result is all the more relevant having been developed against the backdrop of a ‘New Monetary Framework’, as it raises scepticism about RBI’s power to control inflation through altering repo rates. Many economists and policy makers still have their reservations about the efficacy of inflation-targeting in India (ET Bureau, 2008; Balakrishnan, 2014, 2015; Sheel, 2014; Sen, 2015). Our results reinforce their concern.

Policy takeaways

References

Balakrishnan, Pulapre, 2015. “Going beyond inflation targeting”, The Hindu, August 18, 2015

----------------2014. “The case against inflation targeting”, BusinessLine, March 30.

ET Bureau, 2008. “RBI need not focus on inflation-targeting: YV Reddy”, Economic Times, June 28.

Chakraborty and Om Varma, 2015. “Efficacy of New Monetary Framework and Determining Inflation in India: An Empirical Analysis of Financially Deregulated Regime”, WP No. 2015-153, NIPFP.

Government of India and RBI, 2015. “Agreement on New Monetary Policy Framework” http://finmin.nic.in/reports/MPFAgreement28022015.pdf

Government of India, 2015: “Draft Indian Financial code”, Government of India.

RBI, 2014. “Report of the Expert Committee to Revise and Strengthen the Monetary Policy Framework.” Mumbai: Reserve Bank of India.

Sheel, Alok. 2014. “The Unraveling of Inflation Targeting.” Economic and Political Weekly, 49(20): 15-19.

Sen, Pranob, 2015. “Monetary dimensions of the recent Indian inflationary experience”, Ideas for India, IGC. |

(2)

(2)