|

Merit subsidies |

Non-merit subsidies |

Total subsidies |

|||||||||||||||||||

|

State |

Social sector |

Economic sector |

Social sector |

Economic sector |

Social sector |

Economic sector |

Total |

||||||||||||||

|

87-88 |

12-Nov |

15-16 |

87-88 |

12-Nov |

15-16 |

87-88 |

12-Nov |

15-16 |

87-88 |

12-Nov |

15-16 |

87-88 |

12-Nov |

15-16 |

87-88 |

12-Nov |

15-16 |

87-88 |

12-Nov |

15-16 |

|

|

(0) |

(1) |

(2) |

(3) |

(4) |

(5) |

(6) |

(7) |

(8) |

(9) |

(10) |

(11) |

(12) |

(13) |

(14) |

(15) |

(16) |

(17) |

(18) |

(19) |

(20) |

(21) |

|

Andhra Pradesh (Telangana) |

3.8 |

2.8 |

3.3 |

0.1 |

0.1 |

0.1 |

2 |

1.2 |

1.5 |

4 |

4.5 |

4.7 |

5.8 |

4 |

4.8 |

4.1 |

4.6 |

4.7 |

10 |

8.6 |

9.6 |

|

Bihar (includes Jharkhand) |

6 |

4.2 |

4.4 |

0.3 |

0.1 |

0.2 |

1.8 |

1.4 |

1.5 |

7.2 |

5.7 |

5 |

7.8 |

5.6 |

6 |

7.5 |

5.8 |

5.3 |

15.3 |

11.4 |

11.2 |

|

Gujarat |

4.1 |

3.3 |

3.2 |

0.1 |

0.1 |

0.1 |

1 |

0.9 |

0.7 |

4.6 |

2.5 |

3.1 |

5.1 |

4.2 |

3.9 |

4.7 |

2.6 |

3.2 |

9.7 |

6.8 |

7.1 |

|

Haryana |

3.1 |

2.5 |

2.8 |

0.1 |

0.1 |

0.1 |

0.9 |

0.8 |

0.8 |

4.4 |

2.3 |

2.9 |

4 |

3.4 |

3.6 |

4.4 |

2.5 |

3 |

8.4 |

5.8 |

6.5 |

|

Karnataka |

4 |

2.7 |

2.8 |

0.1 |

0.2 |

0.4 |

1.6 |

1.3 |

1.5 |

4.1 |

4.2 |

3.9 |

5.6 |

3.9 |

4.3 |

4.2 |

4.4 |

4.2 |

9.8 |

8.4 |

8.5 |

|

Kerala |

4.7 |

2.9 |

2.8 |

0.2 |

0.3 |

0.3 |

1.3 |

1 |

1.7 |

2.7 |

1.8 |

1.7 |

6 |

3.9 |

4.5 |

2.9 |

2.1 |

2 |

8.8 |

6 |

6.5 |

|

Madhya Pradesh (includes Chhattisgarh) |

4.9 |

4.1 |

4.8 |

0.2 |

0.2 |

1 |

1.7 |

1.1 |

1.9 |

4.6 |

4.4 |

4.1 |

6.5 |

5.2 |

6.7 |

4.8 |

4.6 |

5.1 |

11.3 |

9.8 |

11.8 |

|

Maharashtra |

3.5 |

3 |

2.7 |

0.2 |

0.1 |

0.1 |

0.7 |

0.9 |

0.8 |

2.1 |

2.9 |

2.9 |

4.2 |

3.8 |

3.5 |

2.3 |

3 |

3 |

6.5 |

6.8 |

6.5 |

|

Orissa |

3.8 |

3.4 |

4.5 |

0.2 |

0.5 |

0.5 |

1.5 |

1.3 |

1.1 |

4.7 |

3.6 |

3.7 |

5.3 |

4.7 |

5.7 |

4.8 |

4 |

4.2 |

10.1 |

8.7 |

9.8 |

|

Punjab |

3.2 |

2.7 |

2.7 |

0.1 |

0 |

0.1 |

0.8 |

0.5 |

0.6 |

4.7 |

2.4 |

1.9 |

4 |

3.1 |

3.3 |

4.8 |

2.4 |

2 |

8.8 |

5.6 |

5.3 |

|

Rajasthan |

4.9 |

4.8 |

5.1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0.9 |

0.6 |

0.8 |

6.2 |

2.2 |

3.1 |

5.8 |

5.4 |

6 |

6.2 |

2.3 |

3.1 |

12 |

7.7 |

9.1 |

|

Tamil Nadu |

3.4 |

2.7 |

2.7 |

0.3 |

0.1 |

0.1 |

0.8 |

0.6 |

0.6 |

4.2 |

2.2 |

1.7 |

4.2 |

3.3 |

3.3 |

4.5 |

2.3 |

1.8 |

8.8 |

5.6 |

5.1 |

|

Uttar Pradesh (includes Uttarakhand) |

3.4 |

4.4 |

4.3 |

0.2 |

0.3 |

0.2 |

0.9 |

0.8 |

1.7 |

4.3 |

4.5 |

5.5 |

4.4 |

5.2 |

6 |

4.4 |

4.8 |

5.7 |

8.8 |

10 |

11.7 |

|

West Bengal*** |

3.5 |

3.9 |

2.5 |

0.2 |

0.1 |

0.1 |

0.9 |

0.7 |

1 |

2.7 |

1.9 |

2.2 |

4.4 |

4.6 |

3.5 |

2.9 |

2 |

2.2 |

7.3 |

6.6 |

5.7 |

|

All states* |

3.4 |

3 |

3 |

0.1 |

0.1 |

0.2 |

1 |

0.8 |

1 |

3.5 |

2.9 |

3.1 |

4.4 |

3.8 |

4.1 |

3.7 |

3.1 |

3.3 |

8.1 |

6.9 |

7.3 |

|

Centre* |

0.3 |

0.9 |

0.2 |

0.7 |

1.5 |

1.1 |

0.3 |

0.1 |

0.2 |

3.5 |

1.3 |

1.4 |

0.7 |

0.9 |

0.4 |

4.2 |

2.8 |

2.5 |

4.9 |

3.8 |

2.9 |

|

All states + Centre* |

3.7 |

3.9 |

3.2 |

0.9 |

1.6 |

1.3 |

1.3 |

0.9 |

1.2 |

7 |

4.3 |

4.5 |

5 |

4.8 |

4.5 |

7.9 |

5.9 |

5.8 |

12.9 |

10.7 |

10.3 |

|

All states' average** |

4 |

3.4 |

3.5 |

0.2 |

0.2 |

0.2 |

1.2 |

0.9 |

1.2 |

4.3 |

3.2 |

3.3 |

5.2 |

4.3 |

4.6 |

4.5 |

3.4 |

3.5 |

9.7 |

7.7 |

8.2 |

Notes:

Notes:

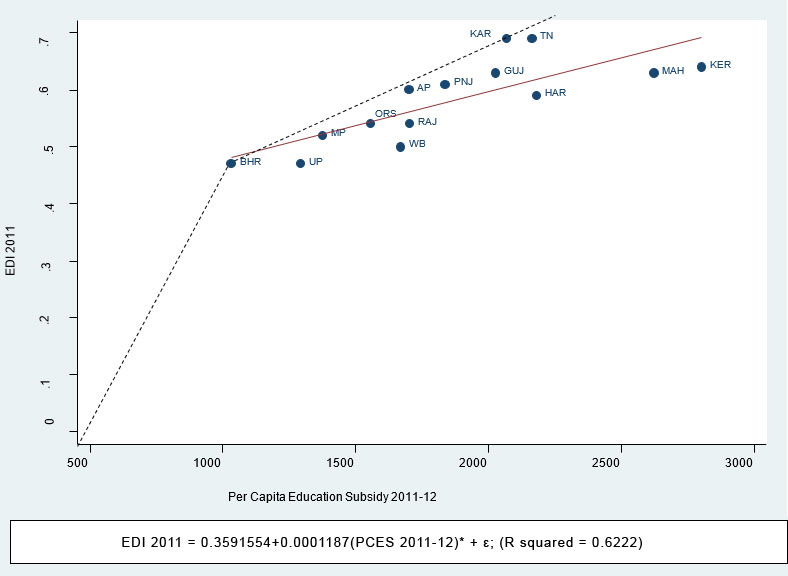

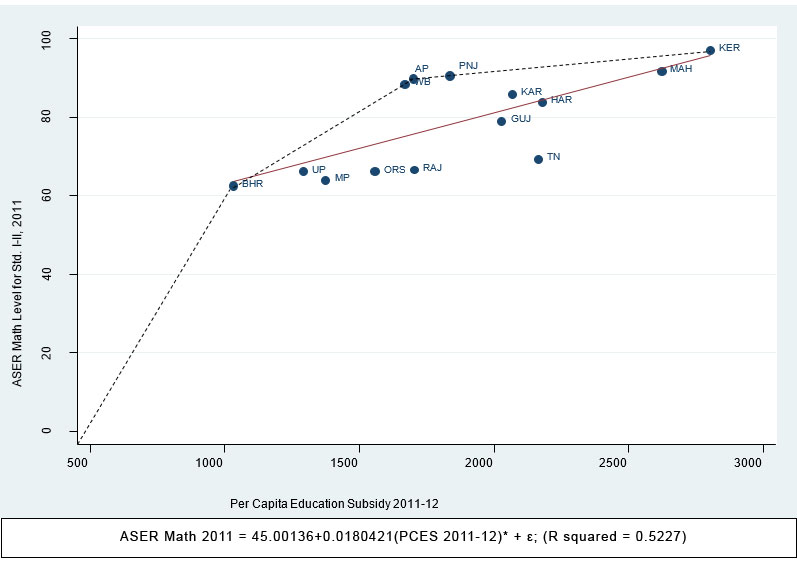

1. Education Development Index (EDI), 2011-12 is a composite educational development index for all schools and managements, based on District Information System for Education (DISE) data, collected from NUEPA (2013), page 43.

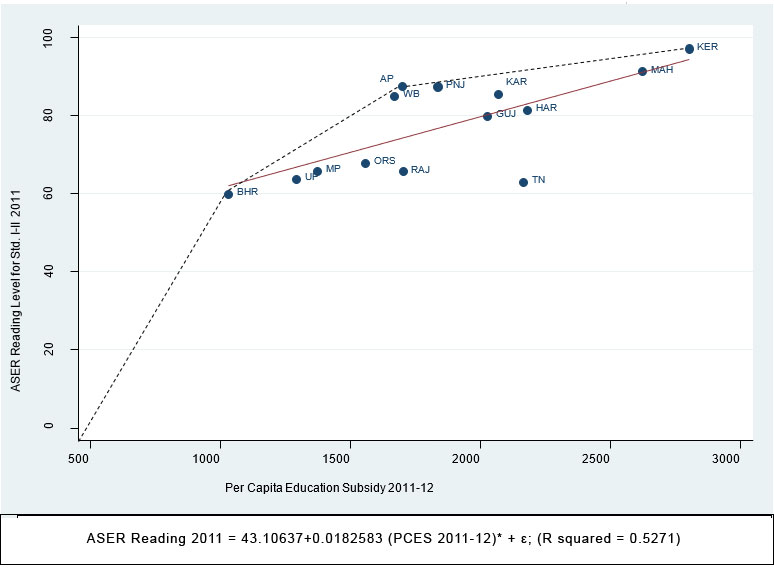

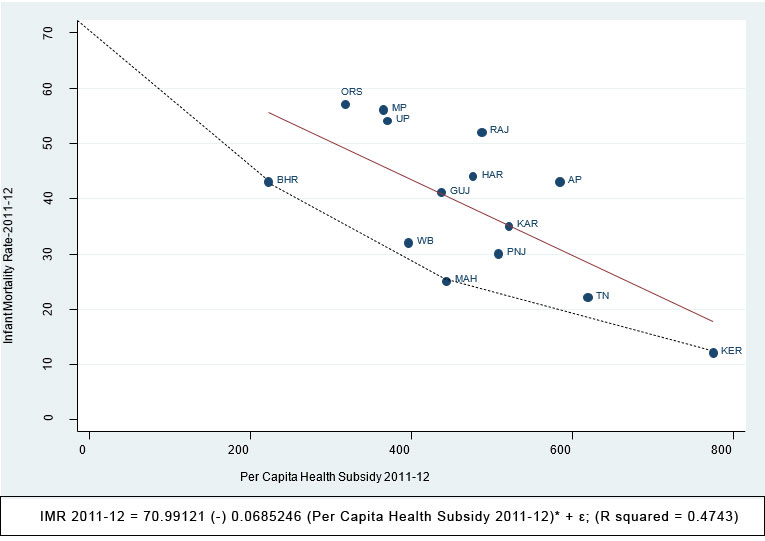

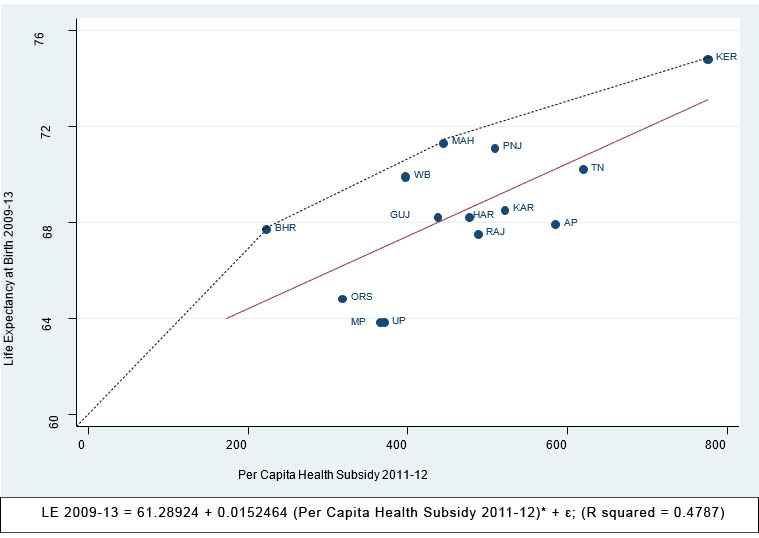

2. The learning indicators are from various rounds of the Annual Survey of Education (Rural) Report (ASER).

3. The concept of a subsidy efficiency frontier is an adaptation of the states’ expenditure efficiency measure developed by Mohanty and Bhanumurthy (2018).

4. Food support through extra free rations has, in fact, been stepped up very significantly, though many citizens without ration cards have not been able to access the free rations. By comparison, steps to provide income support have been very limited so far.

5. See Annexure 7 of the 2020-21 central government receipts budget (Government of India, 2020).

6. PM-KISAN is a central-sector scheme that provides an income support of Rs. 6,000 per year to all farmer families across the country in three equal installments of Rs. 2,000 each after every four months.

7. MNREGA guarantees 100 days of wage-employment in a year to a rural household whose adult members are willing to do unskilled manual work at state-level statutory minimum wages.

Further Reading

Comptroller and Auditor General of India (2019), ‘Accounts of the Union Government – Financial Audit, Report No. 2 of 2019’, 22 January 2019.

Ghatak, M and K Muralidharan (2019), ‘An Inclusive Growth Dividend: Reframing the Role of Income Transfers in India’s Anti-poverty Strategy’, India Policy Forum, National Council of Applied Economic Research, 9 July.

Government of India (2020), ‘Receipts Budget 2020-21’, Ministry of Finance, Budget Division.

Mohanty, RK and NR Bhanumurthy (2018), ‘Assessing Public Expenditure Efficiency at Indian States’, National Institute of Public Finance and Policy (NIPFP) Working Paper No. 225, New Delhi, 19 March.

Mundle, S (2019), ‘An Inclusive Strategy for India to Revive Its Economic Growth’, HT Mint, 17 October 2019.

Mundle, S (2020), ‘Triple Trouble - Coronoavirus, hunger and the economy’, HT Mint, 17 April 2020.

Mundle, Sudipto and Satadru Sikdar (2020), “Subsidies, Merit Goods and the Fiscal Space for Reviving Growth: An Aspect of Public Expenditure in India”, Economic & Political Weekly, 55(5):52-60, 1 February.

Mundle, Sudipto and Satadru Sikdar (2019), “Inclusive Fiscal Adjustment for Reviving Growth: Assessing the 2019-20 Budget”, Economic & Political Weekly, 54(38):32-36, 21 September 2019.

Mundle, Sudipto, Samik Chowdhury and Satadru Sikdar (2016), “Governance Performance of Indian States: Changes between 2001-02 and 2011-12”, Economic and Political Weekly, 51(36):55-64, 3 September 2016.

Mundle, Sudipto and M Govinda Rao (1991), “Volume and Composition of Government Subsidies in India, 1987-88”, Economic & Political Weekly, 26(18):1157-1172, 4 May 1991.

National University of Educational Planning and Administration (2013), ‘Elementary Education in India: Progress towards UEE, Flash Statistics’, New Delhi.

Pratham (2012), ‘Annual Survey of Education (Rural) Reports (ASER), 2011’, New Delhi.