(Co-authored with Lekha Chakraborty)

Does democracy determine public expenditure decisions? With Nobel laureate Hurwicz’s revelation that it is impossible to have simultaneously a balanced budget, Pareto optimality (“you are better off without making anyone worse off”) and an incentive compatibility between Government and the citizens, we turn to pose a question, what exactly determine public expenditure decisions?1

Can a median voter reflect her preference for public expenditure priorities in her voting decisions? Antony Downs in his historic work (Downs, 1957), explained a moment of “democratic collapse” if the “costs of voting” (C) are higher than the voter’s faith in the probability of her vote changing the outcome (P) and the benefits she derives out of her winning (B). William Riker (1968) later balanced Down’s equation by incorporating a new variable “D” which captures the “civic duty” or “rights of citizen to vote” and pre-empted that magnificent embarrassment of C>P*B. A test of this theory prior to the elections would be an interesting evidence-based research.

With the Lok Sabha elections and several state elections lined up in India, we look at the question ‘why do people vote?’ When we posed this to a group of teenagers, they retorted – ‘well, shouldn’t the question be why don’t people vote?’ They were looking forward to exercising their right to vote for the first time and using their agency seemed significant at a very personal level.

In a democracy, elections offer to provide every citizen an opportunity to choose a representative. Creating, correcting and maintaining a democracy is important for every member in varying degrees, and is in essence a public good. We would like to have a fully functional democracy, but the costs at the individual level are high, and each of us would prefer if the others did it for us.

Voting, if thought along this line, is comparable to vaccination.2 The costs aren’t limited to taking the time out to vote, finding your polling booth or standing in the winding queues all morning, but also acquiring information about the candidates, their campaign promises, and most importantly, deciding on the merits of different policies based on what is good for you and your fellow constituents. This is a cognitively demanding task and a formidable challenge for most of us.

Despite this, voters might like to vote to signal that they care about contributing to this public good. No one wants to be a slacker here, especially if others would know about your voting (in)activity as suggested by Dellavigna et al., 2017. A combination of a sense of civic duty, moral responsibility and social pressure brings voters to the polling booths. Once a voter has decided to turn up at the polling booth then she might as well vote for the candidate that she prefers, even if it is a mild preference. And that still makes her go through the cognitively demanding task. One solution is economic voting – you re-elect the party and candidate if the economy is doing well and throw them out if the economy performs badly and this can be seen from our national election data as well (Meyer and Malcolm, 1993). Another option is to look at elections as a chance to throw out an office holder who did not meet your expectations while in office. Or an opportunity to re-elect and retain the ones who did. The extensive literature on voting explains that instrumental motives like these take people to the polling stations (Downs, 1957; Fearon, 1999; Ferejohn, 1986), where voting is a means to bring about an end.

While the general consensus seems to be that as informed citizenry we have a responsibility to vote, there probably is the fact that people appreciate the hard earned right to vote, even if they did not have to personally struggle for it. Additionally voters might also derive satisfaction from the exercise of just going to the polls because the process in itself is valuable (Frey et al., 2004). Addonizio et al. (2007) attributes voter turn out to the ‘festive milieu’ around elections. Voters also try to avoid regret. They do not want to be the only vote missing in avoiding an unpleasant outcome or in achieving their preferred outcome, however unlikely that situation maybe. The motive of the voter turning up thus is to minimize the resulting regret from (not) acting in a particular way (Ferejohn and Fiorina, 1975).

Giving legitimacy to a party or candidate also drives people to the polls. A party taking the largest vote share would have the mandate to bring forth the changes it desires with limited resistance at the Parliament or State Assembly. This is seen in the 2014 national elections where the BJP received such a large mandate that they have had few frictions in getting their agenda passed in the Lok Sabha. However, there is often insufficient evidence of governments with a larger mandate performing better relative to the ones with a smaller mandate (Dahl, 1990).

Local and national elections in most places in India are fought along the lines of religion, caste, and ethnicity. Hindutva has become an unavoidable political reality that all candidates need to address, not just the BJP. In case of religiously/ethnically charged elections it is common to observe voters voting along identity lines. At this stage the act of voting can be interpreted as signaling a group identity or an interest in the group that they aspire to belong.

Vote buying is also not unheard of in the Indian context. Voters respond not to the particular policy positions of the candidates, but to the monetary or material reward that awaits them for their vote or abstention. In a broader sense, vote buying activities fall under voter mobilization campaigns and most of these campaigns results in increasing turnout (Chibber and Ostermann, 2014). Generous gifts including cycles and laptops are a common part of vote buying efforts3 but cash transfers continue to be the most popular.4 Since it is often the poor votes that are bought, there is an additional risk of muffling their voices during elections where vote buying is widespread.

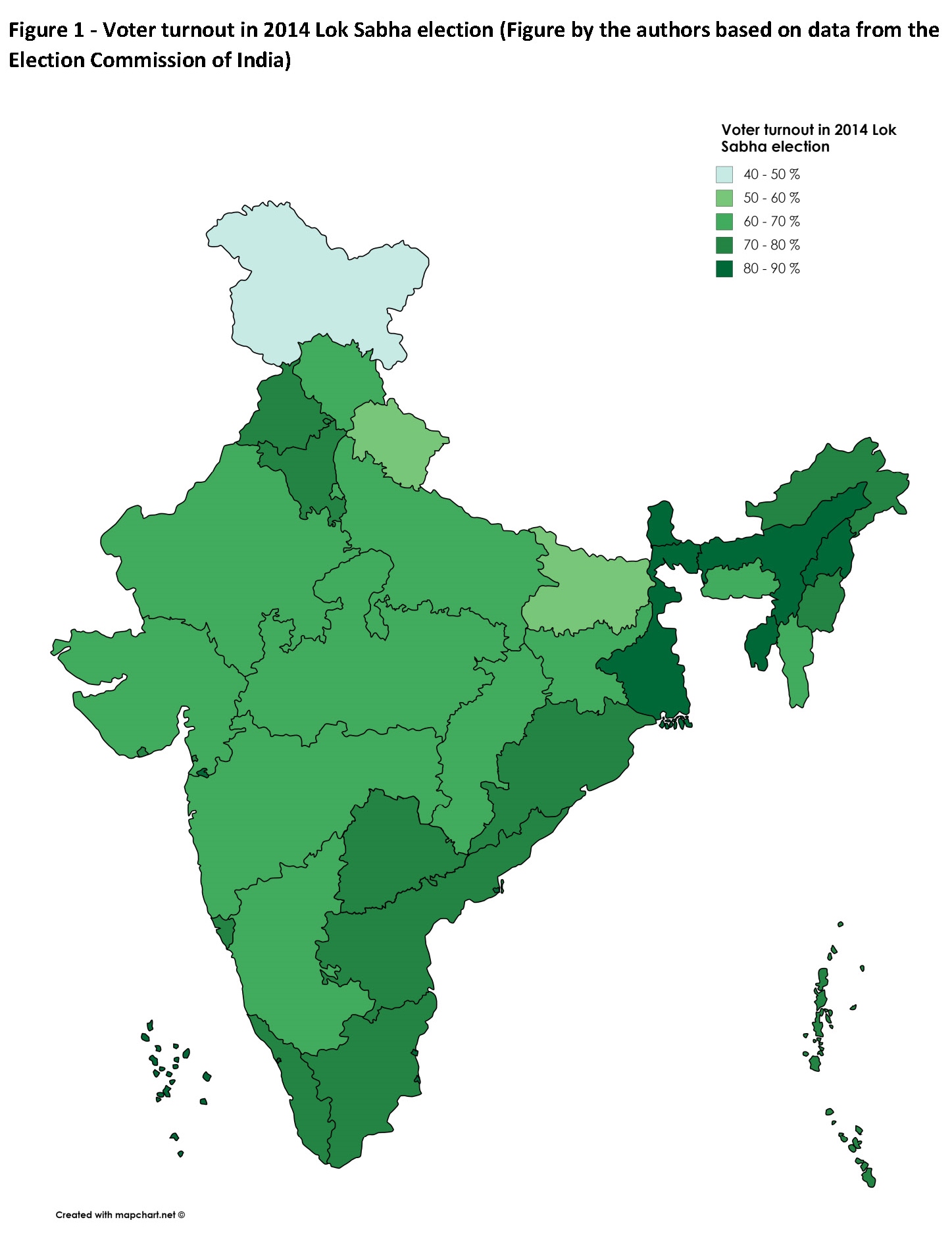

With an average of 66% of eligible voters turning up to vote5 in the national elections (Figure 1. The turnout is higher in state elections) and victory margins close being 15%6 it is rather unlikely that a single vote would change the winner. Still turnout is consistently high in Indian elections compared to most western democracies. Hence voting in itself must be meaningful to the voters. Nevertheless, there are reasons why one wouldn’t vote as well. If a voter believes that they do not have sufficient information to make a call between the candidates or are unwilling to put in the effort or find it too costly to take that effort, they can effectively outsource the decision to others by not turning up to vote. You could also believe that others with a stronger opinion have arrived at that opinion by evaluating the candidates and their policy preferences carefully, given you believe that your preferences are alike. Since 2013, Indian voters are also given the option of ‘None of The Above’7 on the ballot, in case they do not find a reason to vote for any of the candidates, but feel the need to go to the polls, say, to express their commitment to the democratic system.

In addition to the desire to change the election outcome, voters might be engaging in what is called ‘expressing a preference’ (Brennan and Lomasky, 1993). There is always joy in supporting the winning team or the underdog (Simon, 1954). In most cases, participating in the process makes you feel that now you have earned your right to make demands on the government. The list goes on as the reasons that take voters to the polls are innumerous and each voter values them differently. Nevertheless, one of India’s strongest institutions, the seven decades of stable democracy, owes greatly to the consistent and unwavering support and enthusiasm of its millions of voters.

1) But who will guard the guardians? Nobel Prize Lecture, December 8, 2007, Leonid Hurwicz.

https://www.nobelprize.org/uploads/2018/06/hurwicz_lecture.pdf

2) What voting and flu shots have in common - https://behavioralscientist.org/what-voting-and-flu-shots-have-in-common/

3) India elections: A festival of vote buying - https://www.ft.com/content/a9d35821-f2f1-3479-8082-2ce1e6fa79cf

4) Why bribes usually don't buy votes for politicians -https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-india-44080021

5) Election commission of India, data on the 2014 Loksabha election.

6) In the 2014 Lok Sabha election for the Bharatiya Janata Party.

7) Election Commission of India – provision for ‘None of the above’ option on the EVM/ Ballot Paper -

https://www.eci.nic.in/eci_main/ElectoralLaws/OrdersNotifications/NOTA_11102013.pdf

References:

Addonizio, E. M., Green, D. P., & Glaser, J. M. 2007. Putting the party back into politics: an experiment testing whether election day festivals increase voter turnout. PS: Political Science & Politics, 40(4): 721-727.

Chibber, P. K., & Ostermann, S. L. 2014. The BJP’s fragile mandate: Modi and vote mobilizers in the 2014 general election. Studies in Indian Politics, 2(2): 137-151.

Dahl, R. A. 1990. Myth of the presidential mandate. Political Science Quarterly, 105(3): 355-372.

DellaVigna, S., List, J. A., Malmendier, U., & Rao, G. 2016. Voting to tell others. The Review of Economic Studies, 84(1): 143-181.

Downs, A. 1957. An economic theory of political action in a democracy. Journal of political economy, 65(2): 135-150.

Fearon, J. D. 1999. Electoral accountability and the control of politicians: selecting good types versus sanctioning poor performance. Democracy, accountability, and representation, 55, 61.

Ferejohn, J. 1986. Incumbent performance and electoral control. Public choice, 50(1-3): 5-25.

Ferejohn, J. A., & Fiorina, M. P. 1974. The paradox of not voting: A decision theoretic analysis. American political science review, 68(2): 525-536.

Frey, B. S., Benz, M., & Stutzer, A. 2004. Introducing procedural utility: Not only what, but also how matters. Journal of Institutional and Theoretical Economics JITE, 160(3): 377-401.

Lomasky, L., & Brennan, G. 1993. Democracy and decision: The pure theory of electoral preference. Cambridge: Cambridge UP.

Meyer, R. C., & Malcolm, D. S. 1993. Voting in India: effects of economic change and new party formation. Asian Survey, 33(5): 507-519.

Riker William H. and Peter C. Ordeshook, 1968, A Theory of the Calculus of Voting, The American Political Science Review, 62(1): (Mar., 1968), 25-4.

Simon, H. A. 1954. Bandwagon and underdog effects and the possibility of election predictions. Public Opinion Quarterly, 18(3): 245-253.

[The inspiration for this title of the article is from the book by Buchanan and Tullock (1962)]

The authors are Doctoral Fellow in Economics, Max Planck Institute for Tax Law and Public Finance and Munich Graduate School of Economics and an Associate Professor at NIPFP.

The views expressed in the post are those of the authors only. No responsibility for them should be attributed to NIPFP.