(This post was originally prepared for External Services Division of All India Radio, broadcast on July 14, 2018.)

As per the World Bank figures for 2017, India has become the world’s sixth-biggest economy, after US, China, Japan, Germany and UK. India has pushed France to the seventh place. India’s GDP is US $ 2.597 trillion as against $ 2.582 trillion for France.

The United Kingdom, the fifth biggest economy, has a GDP of US $ 2.62 trillion, which is about US $ 25 billion more than that of India. With the ‘Brexit’ conundrum, there is a high probability that India can become the fifth biggest economy in near future. Analysts have predicted that India can surpass Germany and Japan in nominal GDP in dollar term by 2028, and India is also expected to be a “$ 6 trillion economy”—the third biggest economy in the world in the next one decade.

The forecasts of World Economic League Table (WELT) 2018 published by the Centre for Economics and Business Research, London also predicted that India would “leapfrog” UK and France to become the world’s fifth largest economy. The other three countries in the top ten are Brazil, Italy and Canada.

Though India is growing fast, the income inequality issues need to be addressed. India is 126th in terms of per capita income, as per the latest IMF data. Indeed India has a population of 1.34 billion. With India’s population expected to surpass China by 2024, there needs to be an economic convergence across States in India for attaining the “high growth” trajectory.

India’s promising growth trajectory

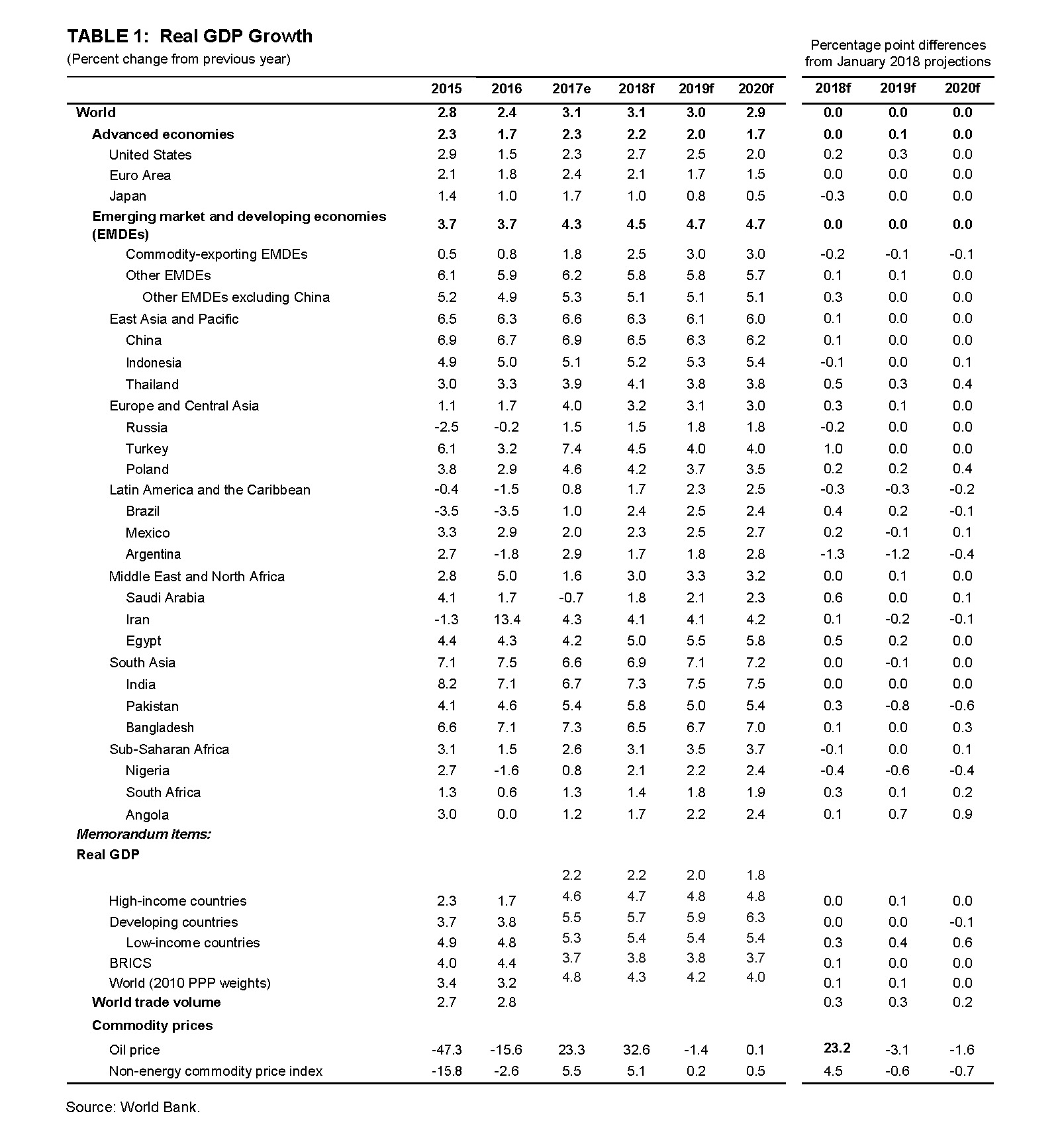

The “Global Economics Prospects” report published by World Bank last month says that India is expected to grow at 7.3 in 2018 and 7.5 in 2019 and 2020. The growth rate estimate is robust and promising, when compared to the GDP growth rate of 7.1 per cent in 2016 and only 6.7 per cent in 2017.

The IMF Report ‘World Economic Outlook’ had also estimated India’s growth trajectory. As per the IMF report, India is expected to grow at 7.4 per cent in 2018 and 7.8 per cent in 2019 and China’s GDP is expected to grow only at 6.6 in 2018 and 6.4 per cent in 2019. The Economic Survey of India has similar GDP forecasts at 7.5 per cent for 2018-19.

The Reports have advised the government to simplify and streamline Goods and Service Tax (GST) to sustain high growth rate. They have also suggested the cleansing process of twin balance sheet crisis–the corporate debt and Non-Performing Assets (NPA) of the banking sector – as well as land and labour reforms for better growth.

Robust economic growth per se cannot address poverty and inequality issues

Despite many challenges, it is heartening to note that India is growing at around 7 per cent when the global economic growth is slated to be only at 3.1 per cent for 2018. However, it has been emphasized that robust economic growth per se won’t be enough to address the pockets of extreme poverty and inequality in India; the macro-policy makers need to focus on ways to enhance human capital formation, productivity and labour force participation.

It is interesting to recall here that the growth rate of India in 2015 was 8.2 per cent as indicated by the World Bank report. India needs to strengthen the fiscal and monetary policies– especially public investment – along with the financial stability in the markets to return to 8 per cent growth. The launch of the Goods and Services Tax (GST) regime and implementation of the Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code (IBC) has had a positive impact on “ease of doing business” in India in the long run.

The Downward Risks to Growth

Though the world economic outlook looks robust now aftermath to global financial crisis, there are considerable “downside risks”. These emanate from increasing international trade protectionism, retreat from globalization, the global financial market volatility and rising corporate debts. Though growing as the sixth biggest economy in the world, India is no way isolated from these “downward risks”.

The views expressed in the post are those of the author only. No responsibility for them should be attributed to NIPFP.